COMME des GARÇONS: abstraction as the foundation of all creation.

The enigmatic Rei Kawakubo, founder of Comme des Garçons, is one of the most visionary and influential designers still active today. She has carefully deconstructed the glossary of fashion to create a new, revolutionary one, in her quest to propose clothes that do not pre-exist, reshaping the very idea of beauty, diverting functions and cuts, proposing a new relationship between the body and clothing. The exploration of the notion of dichotomy, duality or confusion, but above all the desire to shock, are ideas certainly explored by other illustrious figures such as Miuccia Prada, Martin Margiela (or his worthy successor John Galliano at the head of the House) or Marine Serre, but perhaps never with as much force as with Rei Kawakubo. Everything starts from an abstraction, then becomes concept and application.

A name.

Why this French name, written コム・デ・ギャルソン (Komu de Gyaruson) in Japanese? For a long time, the mystery hovered, giving way to the wildest theories. It was during an interview given to Highsnobiety in 2015 that Adrian Joffe – co-founder of Dover Street Market, President of Comme des Garçons and husband of Rei Kawakubo – finally revealed what was hidden behind such a Franco-French name. Some commentators, who suggested that it was in reality just an attempt to gravitate around Parisian haute couture and enjoy a happy and direct association with their image, were disappointed. The most knowledgeable have never dared to equate Comme de Garçons with this, clearly seeing that everything was done to never, near or far, sail in the wake of other contemporary designers, even less French ones. Some had even sensed what was hidden in this name, so strange for a Japanese brand. Iconoclast par excellence, Rei Kawakubo was inspired by the famous song by Françoise Hardy, “Tous les garçons et les filles”, which no longer needs an introduction in France. If this testifies to a certain love for French culture and this vocation to distil a point of view on fashion around the world, there is above all this undeniable affirmation in this name which sounds like a song, a group or a guitar riff: nonconformism as a starting point. This inspiration, which is reminiscent of yéyé rock-pop, is unexpected, to say the least, for a resolutely avant-garde and punk brand, led by the visionary intelligence of its creator Rei Kawakubo since the 70s. But it also reveals the very philosophy of this house. Without highlighting the name of its creator, it also underlies the awareness of collective work, a sort of demystification of the ego, which is nevertheless so present in this universe where dangerous connections with the status of artist are legion. There is a desire to insert oneself into the reality of the present time, without worrying about posterity. However, God knows how much her talent will mark her. Ask her if she considers herself an artist and if her clothes convey messages. Discreet and not very expansive, Rei will answer you in the few interviews she gives, that fashion is an industry, a way of earning a living, and that she is a businesswoman. She certainly is. As evidenced by her many lines and the avant-garde boutiques that have continued to flourish under her green thumb. Rei is a mystery and claims to have nothing to say? So let's dive into her anti-conformist world and discover what her clothes say.

Nonconformism.

Conformism is not part of the CDG language. Rei Kawakubo, born in 1942, grew up in a dark time, marked by the scars of war and its horror in Japan, where fear and austerity permeated the thinking of the population. The country was destroyed, the culture fatalistic. It was glaring in artistic manifestations. It was striking in the seventh art and cartoons. This is certainly what led the designer to shake up the idea of aesthetics, to find beauty in destruction, the unfinished and rags, the irregularity of creation, the worn and the perforated, the ambiguity and the imperfection. A graduate in Art History, she began assisting photographers as a stylist, looking for clothes and accessories. Not finding what she was looking for, she quickly decided to design her own clothes. She defied the very principles of couture at the time when she launched out, revealing her particular taste for expressing a form of poverty and simplicity, in all the richness and complexity of her eye. She expressed a form of revolt, an ode to imperfection, a frontal opposition to conventions, a profound questioning from the beginning, faced with the artifice of clothing, the sexualization of Western fashion. Rei Kawakubo launched the Comme des Garçons brand in 1969 in Japan and the first fashion show was held in Tokyo in 1975, with the opening of the first boutique the same year. In the 1970s, Rei began by making clothes for a woman who she said "does not let herself be influenced by what her husband thinks". In 1978, the Japanese label launched its first men's ready-to-wear line. It was not about expressing social class through luxurious creations, but about making an impression, proposing a new attitude towards clothing, a new philosophy. These are conventions - especially Western ones - on beauty, the construction of a garment and so many others, denounced one by one. The house of Comme des Garçons began with 5 people, who made the clothes by hand or entrusted the making, under their watchful eye, to very small factories. The quantities were tiny, the methods artisanal. Always at the forefront, research is at the heart of the work of the house. Clothes with asymmetrical and deconstructed cuts, a radical and innovative creation, which still influences renowned designers today like John Galliano, Marc Jacobs and Phoebe Philo, by their own admission. But Rei was not really satisfied with her work. She was no longer content to create apron-style denim skirts and patterns inspired by Japanese peasant tradition. She wanted to do something revolutionary, something that would really make an impression, that would really disturb. Rei admits to having a kind of constant anger inside her. She is moving step by step towards the total and meticulous deconstruction of clothing. Monochrome. Black in all its forms. She also wants to get some fresh air far from Japan and challenge Western fashion head-on.

|

|

|

|

|

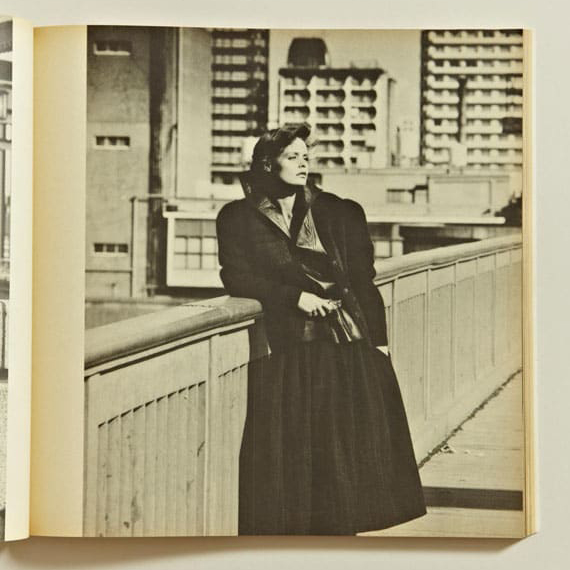

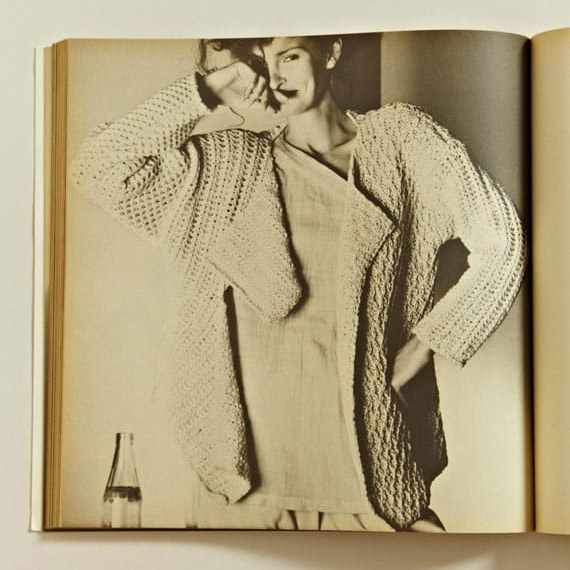

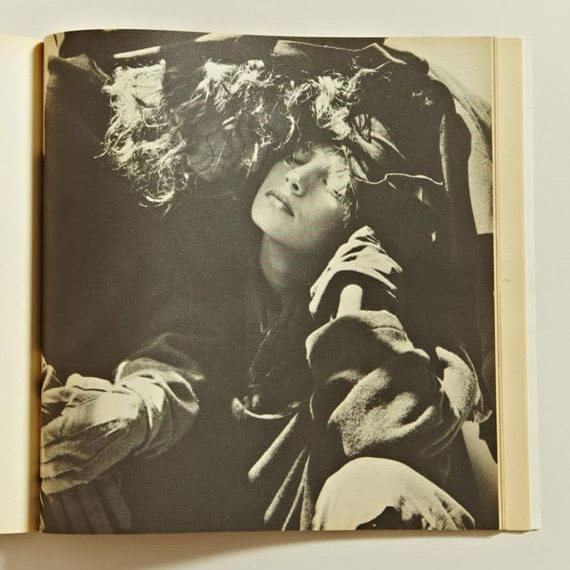

COMME des GARÇONS 1975-1982, book published in 1982 bringing together the first CDG campaigns. |

|

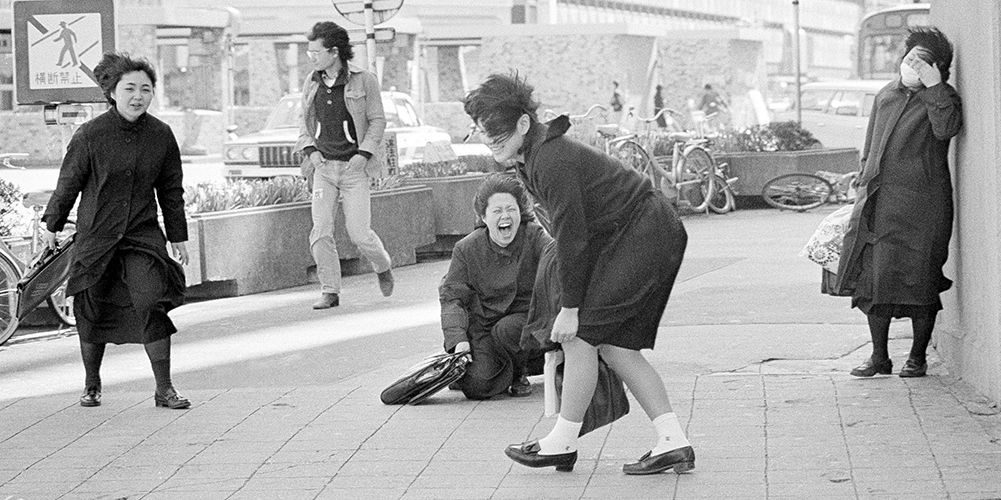

In 1981, the Comme des Garçons collections were launched in Paris, but the house already had a loyal community in Japan, known as the “crow tribe,” “karasu-zoku.” The word “karasu” (烏) means “crow” in Japanese and the word “zoku” (族) means tribe. The rules were simple: create a unique silhouette, made of layers and volumes, symmetries and asymmetries, fluidity, different shades of black or not, not hesitating to sometimes tease androgyny. The “crows” were thus dressed all in black, a “comfortable, strong and expressive” color, in all its nuances, as Rei would say. Their pants were heavy and voluminous, they swallowed up their legs. Turtlenecks, drapes and scarves intertwined with their straight and smooth hair. A fringe revealed a look adorned with dark makeup. Like the British punk movement, whose aesthetic inspires them, this tribe rejected the cliché, the tousled and voluminous haircuts of the 1980s, the flamboyant glamour, the sexualization, the bodies revealed by plunging and close-fitting cuts. They were unconditional fans of the emerging brands of the moment in Japan, CDG and Yohji Yamamoto at the top of the list. Yohji and Rei have a deep mutual admiration and have been travel companions. They quickly realized that their visions were perfectly aligned... They even had a romance. Rei was in her thirties when she met the love of her youth, Yohji Yamamoto. Their couple produced a very special energy and aura, it seems, like those of two feline sovereigns over the jungle, accomplices. They had a stranglehold on the new generation of Japanese design and fashion. The relationship ended in the early 90s.

|

|

Tokyo teenage girls - karasu-zoku (1980s). |

In the late 1970s, both set the stage for the new Japanese stylistic obsession of the 1980s, known as “DC burando” or “designer and character brands,” which fed off the avant-garde of haute couture. Despite this explosive and exponential popularity, Japanese fashion houses refused to be boxed in. On the contrary, they continued to categorically reject tradition and conformity. Their silhouettes were androgynous, asymmetrical, and remarkably unpredictable. Skirts sagged heavily toward the ankles; sleeves were slit and tied with distended ties; fabrics, sometimes luxurious, were crushed, pressed, and crumpled.

The first CDG show in Paris, in 1981, was thus a shock in Western lands. The collection entitled “Lace” almost made spectators feel uneasy. The clothes expressed nothing but destruction, despair and revulsion. Yet they struck a chord, no doubt about it. Nebulous silhouettes paraded, covered in frayed, perforated and spun fabrics, in monochrome dresses. Everything in the idea seems to evoke a defeated and flayed tribe, everything is deconstructed, in total contrast to the work of her contemporary counterparts. Fans blossomed immediately and even if they could not necessarily slip into all these falsely shapeless pieces with faded blacks, they learned something from them: black, darkness as a form of revolution and emancipation. Is Rei an instinctive artist or a fine strategist? Probably both, even if she refutes the first qualifier and likes to present herself as a businesswoman above all. No matter, the street sphere seizes on her fashion. The critics are not mistaken either. Or rather, she pretends to understand and embrace this vision, without really understanding it. Rei is seen more as a renegade. But the more polarizing her collections were, the more successful they were with the public. In 1982, Vogue declared that Rei “uses different blacks, their hue changing depending on the fabric and the light.” Did fashion journalists understand? It’s fair to say that Rei caused a real earthquake in the small world of haute couture of the time and its press. The collection entitled “Destroy” in 1982 revealed models with angry faces, jerky, almost military gaits, and silhouettes with apocalyptic overtones draped in rags crushed from head to toe, completely oversized. Some journalists were stung and decried this show as “Hiroshima’s revenge.” To put it in perspective, in the 1980s, Western fashion was defined by its excess: exaggerated glamour and sumptuous luxury. Designers such as Azzedine Alaia and Christian Lacroix played with the most expensive materials and sought to depict a sexualized feminine physique, all carefully hugged curves. With Rei and his ilk (Yohji, of course), this vision was challenged. It was a form of “aesthetics of poverty” that was developed. The limits of the carnal relationship between the body and the garment were pushed back. Gone were the glamazons of Gianni Versace and the broad shoulders of Thierry Mugler. Volumes became wild, cuts became more sleazy and broke away from pre-established codes. Critics called fashion “apocalyptic.” Then, to describe CDG and Yohji Yamamoto, the press ended up inventing a category in its own right: “Hiroshima chic” or “the bag lady”. Critics, even if often incredulous and perplexed, definitively imposed it at the forefront of Japanese fashion, with Yohji Yamamoto or ISSEY MIYAKE. Constantly shocking and perpetually questioning, that is the philosophy. The 1980s were also the time of the rise of the deconstructivist movement in architecture with Zaha Hadid, Frank O. Gehry, Daniel Liebeskind, Peter Eisenmann, Günter Behnisch, Bernard Tschumi and the Viennese group Coop Himmelblau. Their philosophy is in total contrast with traditional architecture, they deconstruct all its codes to write a new page. The parallel was made. The most knowledgeable will compare the movement launched by Rei and Yohji to this one.

Forty years later, this radical rejection of established fashion norms is considered one of the key moments of modern fashion. The CDG shows are still one of the most anticipated moments of Paris fashion week and a real spectacle. Moreover, Rei does not hesitate to stage famous people in these real live shows that are her shows (but especially for the Men's collection, who knows why): Francesco Clemente, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Robert Rauschenberg and even Alexander McQueen have paraded for her. Even if she denies being an artist, the boss of the empire, constructs clothes that look more like works of art than fashion creations. She reshapes bodies, magnifies movements, through a clever mix of cuts and materials. She constantly reinvents. Surprising growths modify the curve of a back, stifle a neck, contradict the design of the body and the movement of a shoulder or an arm. She surprises. She challenged the very idea of masculine or feminine clothing through her vision, her use of references and concepts, volumes and techniques, in shows that resemble real abstract spectacles. In 1994, when the entire audience, all dressed in black, discovered the first looks of the show, she was stunned. It was an explosion of colors and an ode to fluidity. A kaleidoscope that we find in the Men's collection the same year, but only to adorn their feet with colorful slippers and a few touches that leave a scent of oriental groceries. The rest is like the cliché of the urban man pushed to its paroxysm, between white shirts and rigorously black cotton suits. In 1995, she adorned the catwalks of the Men's show with baggy cuts, striped and sometimes numbered work jackets, in the rawest materials. The models were shaved. This is undoubtedly reminiscent of the outfits worn by prisoners in concentration camps. The press was offended. In 1996, shapes straight out of Picasso paintings took center stage. It was surreal, the growths were legion and deformed all the bodies in psychedelic colors, like a voluntary distortion of reality to prove that she – Rei – could control its perception. Everything was carefully wrapped in tulle. Nothing other than the qualifiers “unwearable” and “strange” appeared in the press. The silhouettes of spring 1997 had the effect of inflated and patched balloons, of an entire wardrobe placed in abyss and superimposed. “Beyond clothing” could very well have described her fall/winter 2006-2007 collection. Rei Kawakubo says she doesn’t feel comfortable when the collection she presents is too well understood. She said so after her 2011 collection “White Drama” was too well understood as the deconstruction of that special day of celebrating a union (which featured some notable pieces of mastery, by the way). The “Monster” collection, from fall/winter 2014-15, reconnects with what she loves: to shock and perplex at first glance. She presented tubular appendages woven, knotted, twisted and braided, in dark shades of wool knit, as a reaction to the madness of humanity, to this fear rooted in all of us, this feeling of going beyond common sense. For her, this could only be transcribed in a grandiose figure, however ugly or beautiful it may be. This desire to challenge established beauty standards and this anger are still palpable. This is how she has built an empire step by step, becoming the reference and the main source of inspiration for entire generations of designers, constantly challenging Western concepts of body shape, body image, gender and sexuality, redefining the relationship between the body and clothing. She is said to be an eternal loner, even if she insists on the collective in her work. Moreover, Adrian Joffe, her husband, does not live under the same roof. However, she does not only inspire, she knows how to share.

|

|

|

|

|

COMME des GARÇONS Women's Fashion Show Fall/Winter 2018 |

|

Sharing.

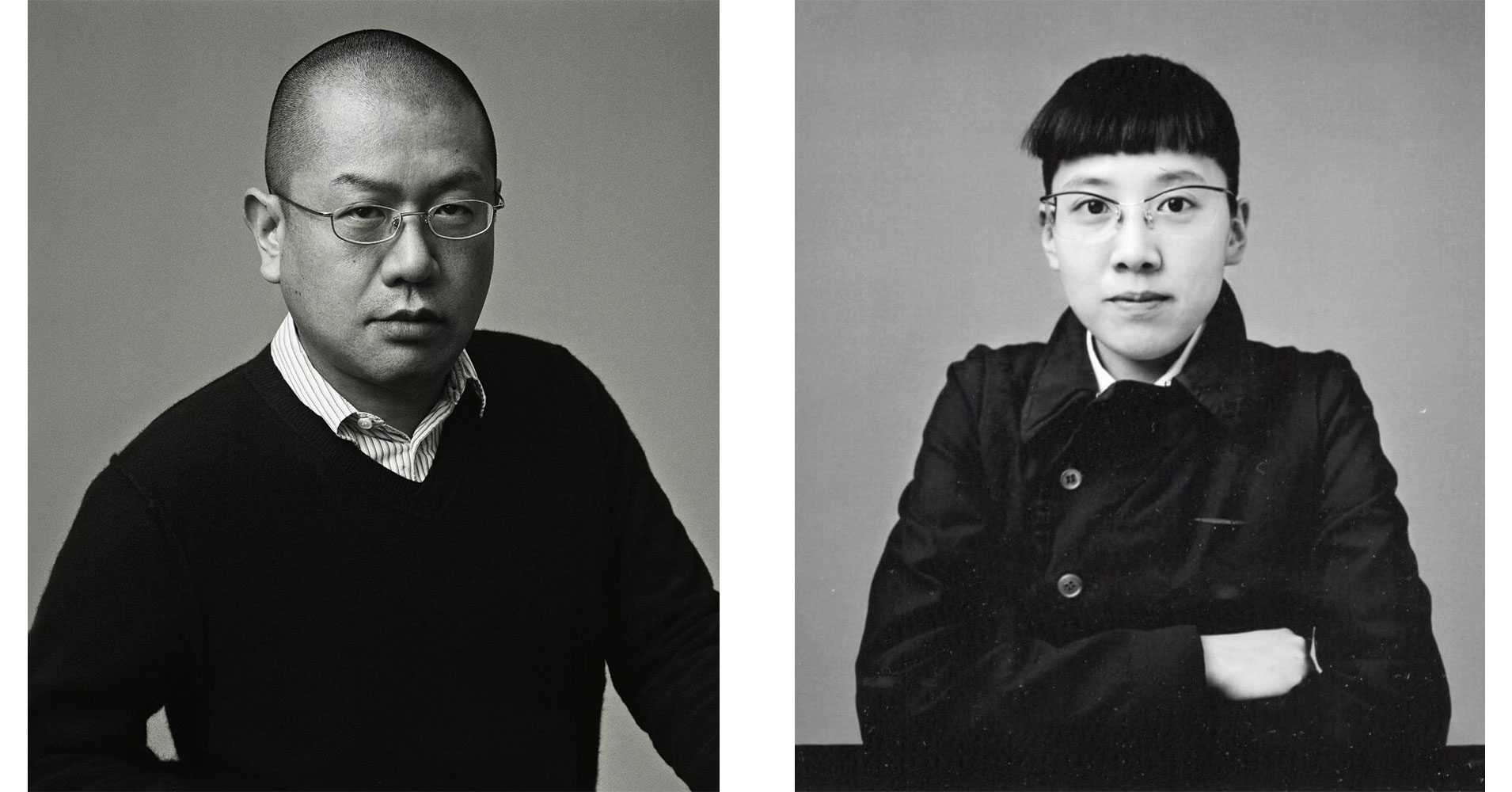

Far from monopolizing the creative direction of the brand, Rei Kawakubo surrounded himself with talented designers, such as JUNYA WATANABE, Tao Kurihara, Fumito Ganryu, Kei Ninomiya and Chitose Abe who would create the brand sacai, who would at the same time launch their own eponymous brand under the Comme des Garçons label. Protégés who will be able to demonstrate their belonging to this lineage, all the heritage of this sensitivity and this deep passion for the concept.

Junya Watanabe, for example, joined the Comme des Garçons family after graduating from the prestigious Bunka Fashion College in Tokyo in 1984. He began his apprenticeship as a modeler with his mentor. Aware of his abilities, Rei quickly handed over the creative direction of the Knitwear line to him in 1987, before he took over the reins of the Men's line. His talent exploded. Rei, eager to push her abilities and have healthy and stimulating competition of her own, suggested that he launch his own line within the house. This was the birth of "Junya Watanabe Comme des Garçons", which paraded in Tokyo in 1992 and the following year at Paris Fashion Week. Each creation, each fashion show, is a performance in its own right. Aficionados know this. Junya has something more pragmatic about him than Rei. He produces clothes that reveal great complexity and a great sensitivity for design, while being practical answers to the demands of a modern lifestyle. He excels in the art of defying conventions. Incredible technical prowess is carried by many of his creations. His exceptional cuts and his passion for innovative and futuristic fabrics are celebrated. His interpretation of streetwear, denim, sportswear, uniforms and fashion history are adopted. Generally, Junya likes to question a particular material, throughout the same collection. This is his creative process. It is from 1999 especially, that all his genius is revealed, in a collection made from technical materials, resistant to extreme conditions. Unheard of in Haute Couture. In 2000, dresses of incredible lightness and technicality appeared, with shapes straight out of his soaring imagination and the press struggled to find its words in the existing lexicon. Without doubt one of his finest feats of arms, among others. In autumn-winter 2009-2010, he played with the volume and lightness of nylon quilted with elegant down (this is also the baptismal name of the collection), presenting a series of black dresses and puffy skirts, matched with jackets with gold chain link closures. For autumn-winter 2006-2007, he patched and merged real army fatigues, sprinkling them with green lace, to concoct dresses decorated with rivets, zippers and snaps, pointing out absurd openings. It is a collection that he calls "Anti, Anarchy and Army." He also developed a ready-to-wear line for men in 2001 - Comme des Garçons Junya Watanabe Man - which found fans all over the world. A commercial success.

Tao Kurihara joined the family in 1998, after studying fashion design at Central Saint Martins, London. Rei enabled her to launch her own label Comme des Garçons in 2005 in Paris. Her approach is more like Rei’s. It is full of intuition. As she says, “I start with a new technique, which manipulates fabric in a way that I have never done before and then asks me to explore what kind of clothes I can make from it.” Tao Kurihara’s early work displays a hybrid design, combining knitwear and lingerie. In 2005, she created trench coats from knitted lace handkerchiefs sourced from around the world. Later designs, including the 2007 and 2008 shows, have featured an increasingly complex design of flowing, airy dresses and one-piece suits. Her aesthetic is one of ultra-femininity, almost sensitive and delicate, of a complex but soft world. Elements borrowed from lingerie are often explored and reworked, bedspreads and handkerchiefs overdyed too. It is a ballet of lace, ribbons, ruffles, prints and tulle and ribbons. It is an experimental exploration of femininity, which can be compared to that pursued by her mentor. For her penultimate show under the CDG label, in spring-summer 2010, it is a condensed collection of dresses created by the sole twisting of strips of fabric with floral print and through knots, all rigorously done by hand. There is in her and in her aesthetic a certain offbeat punk side and a desire to constantly question the rules, often self-imposed, those of design above all. A desire to create concepts. This is central to Comme des Garçons.

Junya Watanabe, Tao Kurihara, Fumito Ganryu and Kei Ninomiya

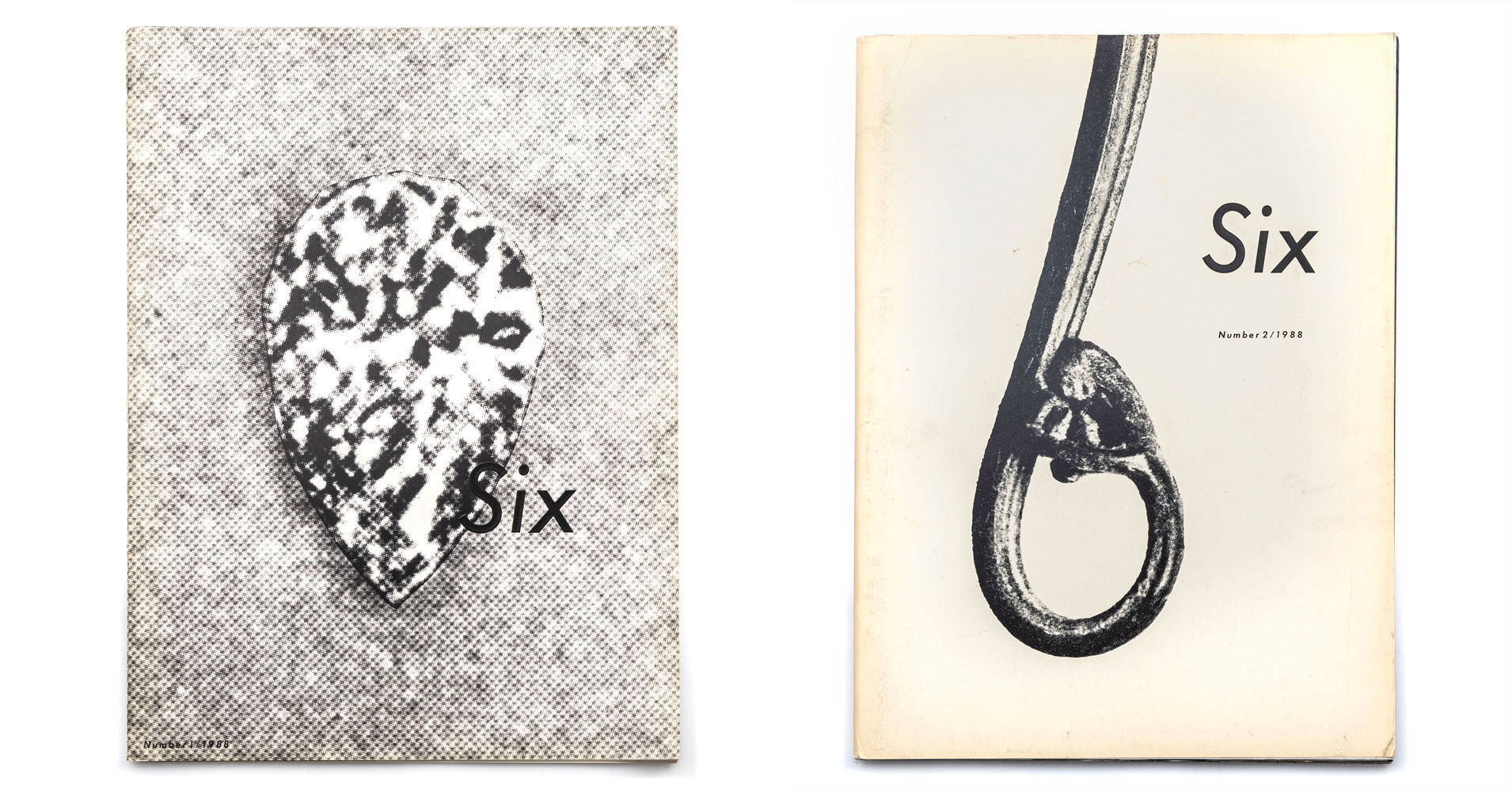

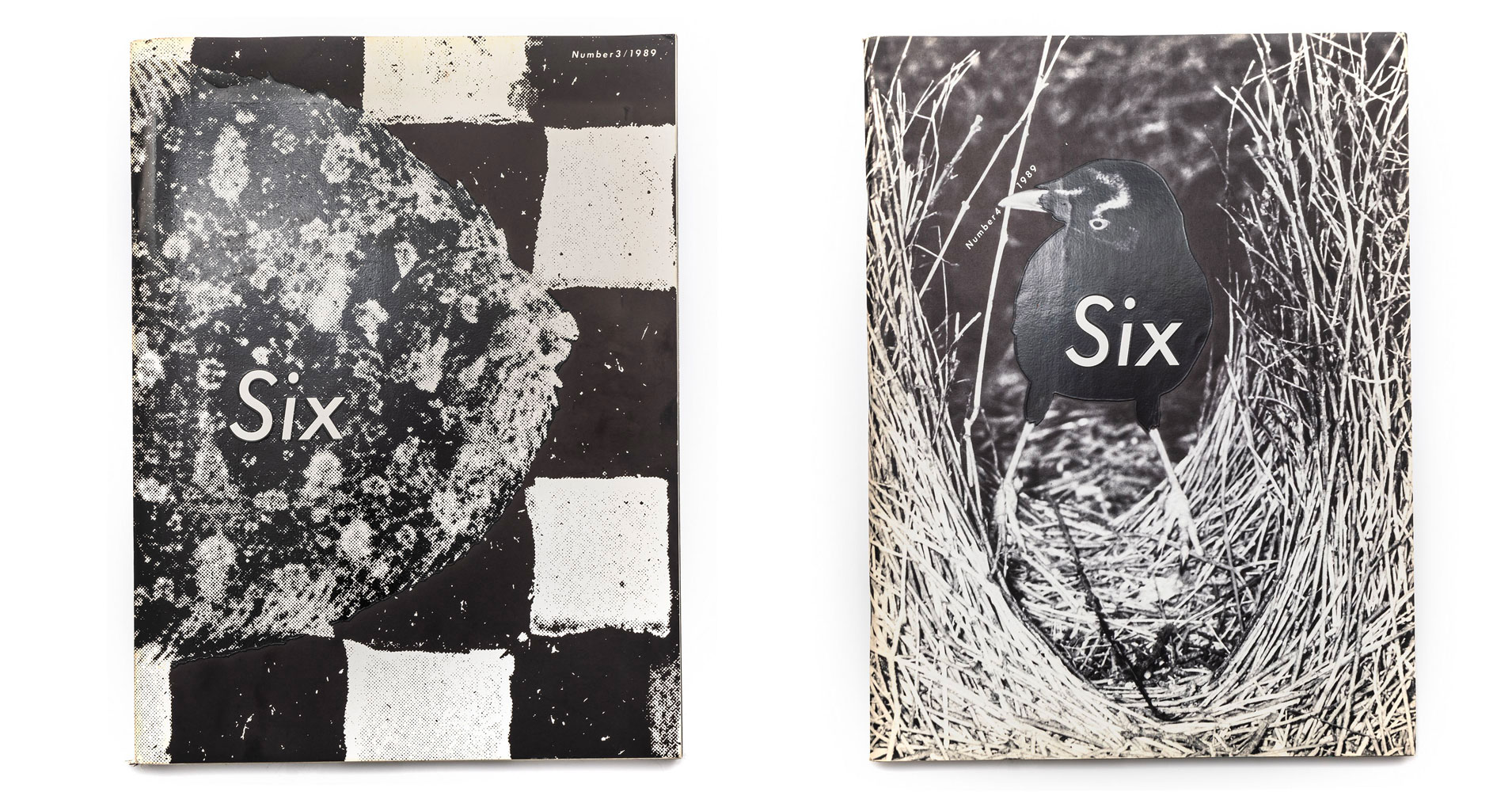

Six.

Six as in sixth sense or this concept developed by Rei, to go and conquer it. In 1988, fifteen years after founding Comme des Garçons, she launched Six Magazine. A biannual, developed in collaboration with designer Tsuguya Inoue and editor Atsuko Kozasu, entirely dedicated to visual exploration. Images and just a few brief text inserts here and there, to illustrate differently the house's collections, which were revealed at the same time on the catwalks. Oversized, unstapled pages that bear witness to the real impact that Rei and Comme des Garçons had on the world of fashion and not only. It is not just a catalog of references, but a notebook, a logbook, of Rei's inspired mind. She says in fact that she only drew inspiration from her imagination in all of her work. Unfortunately, the life of this concept, considered by many to be an aesthetic treasure, was not eternal. Only eight issues were published. They are now being snapped up at a high price. But this magazine has still taken the time to highlight illustrious contributors who have collaborated with Rei, such as the designer Azzedine Alaïa and the famous photographer Peter Lindbergh, but also the artist duo Gilbert & George, Minsei Tominaga, Bruce Weber and Kishin Shinoyama. In the New York Times, during one of his rare interviews, Rei explained his vision of the magazine: "Haute couture must keep the mystery about itself. This is the next step: the visual representation of the collection, purely for the image."

The empire.

The Comme des Garçons galaxy is undoubtedly sprawling and multidimensional. From high-end artisanal clothing for men and women, to entry-level unisex cotton T-shirts, to fragrances, accessories and merch, there is no product category that “Comme des” (or “Comme” for short) doesn’t manage to successfully reach. The list of brands in the group is long: Comme des Garçons, Comme des Garçons Homme Plus, Comme des Garçons Homme Plus Evergreen, Comme des Garçons Homme, Comme des Garçons Homme Deux, Comme des Garçons Shirt, Comme des Garçons Shirt Boys, Comme des Garçons Knitwear, Comme des Garçons Comme des Garçons (or “Comme Comme”, which gradually replaced Comme des Garçons Robe de Chambre), Comme des Garçons Junya Watanabe, Comme des Garçons Ganryu (which sadly ended recently, Fumito Ganryu launched his eponymous line outside the CDG galaxy in late 2019), Comme des Garçons Tao (as we saw previously), Noir Kei Minomiya, Gosha Rubchinskiy (plus a protégé of Rei’s husband, Adrian Joffe, who is president of Dover Street Market and Comme des Garçons), CDG, Play Comme des Garçons (the heart that even the uninitiated know), Black Comme des Garçons, Wallet Comme des Garçons, Comme des Garçons Parfums and Good Design Shop… An empire. Of course, there’s one place to immerse yourself in this universe: the CDG stores. But not only that. The list of the empire’s properties wouldn’t be complete without Dover Street Market (DSM), created by Rei and her husband Adrian Joffe as an outpost for experiential retail, a large space showcasing the entire Comme des Garçons galaxy, as well as a number of hand-picked third-party brands. The first store opened in 2004, on Dover Street in London’s Mayfair district. In 2006, Dover Street Market Ginza opened in Tokyo, followed in 2013 by a store in New York. More recently, Dover Street’s presence has expanded to Singapore, Beijing, Los Angeles and online, while the London brand has migrated to Hayward Street, near Piccadilly Circus. A store dedicated to perfumery has opened in Paris. Today, Dover Street Market is considered the world reference for the biggest fashion retailers, largely thanks to its unrivaled selection of CDG group brands, but also its eye for other brands. A well-crafted concept. Moreover, “Comme des” is renowned for having created the concept of pop-up stores, temporary boutiques, well before it became fashionable among major brands. Their first “guerrilla” store was born in Berlin, to sell stocks from previous seasons, in order to offer this city, off the radar of the fashion sphere at the time, a little of their universe. It was such a success that the operation was reproduced elsewhere (Reykjavik, Athens, Beirut and Los Angeles). The Play line also worked in particular with pop ups. The group has perpetually evolved, adapting to the modern world. For example, with the 2008 crisis, rather than selling off their creations to maintain turnover, they decided to create the Black line with pop-ups, which simply reproduced the best-sellers, with black as a must, at lower prices. It was also one of the first luxury brands to chain together collaborations (with success, moreover). The first was with Nike, to create the “Junya Watanabe Comme des Garçons x Nike Zoom Haven” sneaker, a brand with which collaborations have followed one after the other. But we can also note Converse, Vans (with Colette and Raf Simons or Supreme), Supreme, H&M, Trickers, Repetto, etc.

Consecration.

In almost half a century since its arrival in Paris in the 1980s, Comme des Garçons has distilled some of the most powerful images in the history of fashion with campaigns that have not aged a day and revolutionized fashion, being both reserved for the initiated and accessible to others. In 1987, Vogue predicted that Rei Kawakubo would be “the woman who will lead fashion in the 21st century”, as some journalists were beginning to understand her work. Indeed, her work remains among the most profound on the catwalk and she continues to redefine the possibilities of clothing every day, at the age of 77, working hard in her ateliers, as in the beginning. Her approach – radical and uncompromising – has revolutionized expectations of fashion, prioritizing ideas, concepts and creative processes. She has influenced an entire generation of designers. For fashion historian Colin McDowell, author of the excellent Fashion Today, Rei Kawakubo’s impact on clothing “was more subtle and profound than any other trend in the last fifty years,” and he ranks her, along with Madeleine Vionnet, among the two most influential figures in 20th-century fashion. In fact, Rei Kawakubo is only the second designer to have had the honor of a retrospective at the Costume Institute of the MET during her lifetime, after Yves Saint Laurent in 1978 (who was later pilloried for being too “commercial,” whatever that implies). As Rei astutely and ironically points out in the 2017 exhibition catalog: “All art is commercial. It has always been commercial—today, more than ever.”

Yet there is nothing “commercial” about the exhibition. A hundred outfits are integrated into a structure designed and built under his orders in advance, divided into non-chronological and antinomic categories such as Top / Bottom, Absence / Presence, Object / Subject, Fashion / Antifashion or Body Meets Dress (the body meets the garment) / Dress Meets Body (inversely), a section taken from a show that had completely reinvented the female body and clothing – and thus, the way of sexualizing the female body in fashion – by large excrescences in improbable places, draped in soft gingham. This has, if need be, opened Comme des Garçons to a new audience.

Here, to close this beautiful adventure to which we can only wish more beautiful days, are a few rare words that Rei Kawakubo was kind enough to share.

"I never intended to start a revolution. I only came to Paris with the intention of showing what I thought was strong and beautiful. It turns out that my notion was different from that of others."

"Creation is not something that can be calculated."

"Comme des Garçons is a gift for oneself, it is not something to please or attract the opposite sex."

"Fashion is something that you attach to yourself, that you wear, and through this interaction, its meaning is born. Without wearing it, it has no meaning, unlike a work of art. Fashion is, because people want to buy it now, because they want to wear it now, today. Fashion is just the present moment."

"My intention is not to make clothes. My mind would be too narrow if I only thought about making clothes."

"If I do something that I think is new, it will be misunderstood, but if people like it, I will be disappointed, because I have not pushed them enough. Maybe the more people hate it, the newer it is. Because the problem is that humankind is afraid of change. The place I always look for, because to keep the business going I need to compromise a little bit between my values and the values of the customers, is the place where I do something that could almost - but not quite - be understood by everyone."

"The more people who are afraid when they see a new creation of mine, the happier I am. I think the media has a part to play in the fact that people are becoming more and more conservative. Many media have created fertile ground for uninteresting fashion to flourish."

"What I want to express is a feeling - various emotions that I feel at a given moment - whether it's anger, hope or something else, and from different angles. I build a collection and it takes concrete form. That's probably what seems conceptual to people because it never starts with a specific historical or geographical reference. My starting point is always abstract and multi-layered."

"Comme des Garçons from now on, it's no longer about outwardly obvious design and expression, but about content design, about what's deep down (in us)."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Campagnes COMME des GARÇONS |

|